A slightly different version of this story first appeared in the Boulder Weekly.

When James Sines shopped for homes in 2007, he thought he knew how to pick a neighborhood that would never be drilled for oil or gas. His nephew, a geologist, told Sines to ask the real estate agent showing a house in Broomfield’s Anthem development whether the deed included subsurface mineral rights. The real estate agent’s answer was vague. Sines pressed the agent, and learned that the mineral rights beneath the otherwise spacious floor plan would not belong to him.

Sines crossed the highway to a development called Wildgrass where orderly rows of executive homes were under construction. “The first question I asked was, `Do I own the mineral rights?’” recalled Sines. The answer was yes, and he bought the house.

Nearly a decade later, Sines, a manufacturing consultant, learned that in Colorado, owning your mineral rights doesn’t necessarily protect you from drilling. An arcane provision in Colorado law allows energy companies to drill under residential communities even when homeowners own their mineral rights but don’t want to lease them.

It’s called “forced pooling.”

Forced pooling, Sines and his 509 Wildgrass neighbors have learned, gives oil and gas companies the right to drill under their property, as long as the company makes a “reasonable” offer to mineral rights owners and at least one homeowner signs a lease. Even if the rest of the community opposes the development and declines to lease their rights, an energy company can apply to the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) for a forced pooling order, and the COGCC will almost certainly approve it.

Forced pooling came to Wildgrass in the form of Extraction Oil & Gas, a company specializing in developing wells near Colorado housing developments – and generating conflict in its wake.

Wildgrass residents first heard about Extraction in a letter from High West Resources, Ltd. dated June 24, 2016. The land resource company, which represented Extraction Oil & Gas, LLC, offered to lease each homeowner’s mineral rights in exchange for a $500 signing bonus and a 15 percent royalty on an undisclosed amount of potential oil and gas revenue. The letter ended with this pressure-infused sentence, in bold. “This offer to lease is valid for fifteen (15) days from the date of this letter.”

Some Wildgrass residents assumed the letter was a Front Range version of a Nigerian get-rich scheme and tossed it. Others knew they owned mineral rights under their homes and had no intention of leasing them to High West, Extraction or anybody else. Some say they never received the notice at all. A handful signed the lease. Still others were worried, even panicked, especially when they found out that Extraction was threatening Wildgrass residents with forced pooling if they didn’t sign.

For Sines, it was a sign he’d better sell. “It can’t be good for property values,” he said, standing near the “For Sale” sign planted near his curb on an early fall day. “There can’t be a return from this leasing that’s more than the impacts on the community’s property values.” He said he has too much sunk into the house to watch his equity disappear, and doesn’t believe that any politician, state regulator or lawyer is going to ride in on a white horse to help. “We’re definitely getting bent over,” said Sines. “I’m outta here.”

For many others in Wildgrass, however, it was time to fight back.

![The Lowell Pad, where Extraction Oil & Gas plans a 42-well site, between Wildgrass and Anthem developments.]()

The Lowell Pad, where Extraction Oil & Gas plans a 42-well site, between Wildgrass and Anthem developments.

1889, meet 2016

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court established the “rule of capture” in 1889 during the heady early days of the oil explosion, differentiating an underground mineral right from a surface landowner’s right. The idea, put simply, was “drillers keepers”— whoever stuck a straw into the ground and sucked oil to the surface could keep it, even if the oil flowed from under a neighbor’s property.

That didn’t work so well. (Remember the Daniel Day-Lewis line, “I drink your milkshake,” from There Will Be Blood?) The law evolved to address the increasing number of conflicts that emerged. One result was to further codify this notion of “split estates,” where one person could own surface property, but another person (or corporation) could own the mineral rights below.

As oil companies launched their 20th century catapult to become among the most profitable businesses in history, they hired sophisticated lawyers and lobbyists to write legislation that favored their industry. They ensured those laws would pass by using brute political force and slick public relations campaigns. Ensuing laws gave mineral owners preferential rights to force surface owners to accommodate their rigs, often with disastrous consequences to the surface owners’ domestic tranquility, not to mention their water quality and health.

(The oil and gas industry recently spent millions of dollars in Colorado to prevent two initiatives from getting on this year’s ballot that would have placed some limits on oil and gas development, and spent millions more to pass November’s “Raise the Bar” initiative that will make future citizen-led ballot issues even tougher to pass.)

Later, the concept of “compulsory pooling” surfaced, giving oil and gas companies the right to access underground hydrocarbons even when they didn’t own them or acquire the rights to lease them. The idea, said CU Law School Thomson Visiting Law Professor Bruce Kramer, was to ensure that a homeowner who didn’t want oil and gas rigs on their property “cannot deprive their neighbor the right to develop them.”

Ironically, when two cities in Kansas passed the first “compulsory pooling” laws in 1927, according to Kramer’s analysis, they aimed to limit the number of urban drilling rigs. At the time, Kramer said, “thousands and thousands of wells were being drilled,” since a mineral owner risked having a neighbor drink the mineral owner’s milkshake if they didn’t sink a well themselves. Forced pooling, Kramer said, allowed multiple mineral owners to share the financial benefits of drilling without creating an inefficient mess — or being held hostage by holdouts.

Fast forward to the drilling boom of the last decade, when a combination of new, horizontal drilling technology and more sophisticated hydraulic fracturing (fracking) techniques opened up vast frontiers of previously unrecoverable deposits of oil and gas. Oil and gas companies received exemptions from complying with provisions of federal environmental laws such as the Clean Water Act, as famously happened in 2005 when then-Vice President Dick Cheney’s controversial “Energy Task Force” allowed energy companies to withhold information about the toxic chemicals they used for hydraulic fracturing.

States like Colorado also legislated that oil and gas companies would receive preferential treatment on multiple fronts. The laws allowed energy companies to create larger and larger milkshake pools and to snake their straws for miles to access almost any fuels they wanted, including near schools, water sources – and under residential communities like Wildgrass.

Over the past decade, residents, cities and counties facing oil and gas development in their backyards have objected. In case after case around the state, they have been systematically overridden: by state law, COGCC regulations and the courts – all interpreting laws that the industry essentially wrote. In May 2016, the state Supreme Court also ruled in favor of the industry by invalidating voter-approved restrictions on new oil and gas developments in Ft. Collins and Longmont, with repercussions for Lafayette, Boulder County – and Broomfield.

“The government is not supposed to pick favorites,” said attorney Matthew Sura, who represents Wildgrass and other communities facing forced pooling and neighborhood drilling. “But the oil and gas industry is clearly their favorite here in Colorado.”

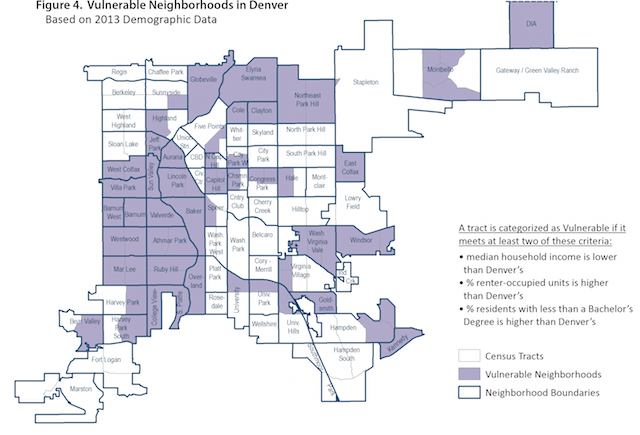

With the support of the COGCC’s interpretation of its statutes, operators in the state are increasingly using forced pooling as a tool to work in more densely populated areas. Extraction Oil & Gas has 20 pooling applications on the COGCC’s December docket, many of them in and around the city of Greeley. A conservative estimate indicates there are at least 15,000 potentially affected mineral owners in those 20 applications alone, including family estates and corporate owners. Statewide, according to COGCC Director Matthew Lepore, the Commission issued about 540 orders per year between 2012 and 2015. About 40 percent of those were pooling orders, where multiple mineral owners were consolidated into one company’s drilling proposal, with and without the owner’s consent. The COGCC does not track how many owners voluntarily signed leases, and how many were “force-pooled.”

In an email response to questions, Lepore wrote that the Commission has not yet encountered a situation where “all or nearly all” of a large number of mineral owners in a spacing unit “are united in opposition to leasing their minerals.” He said that if there is significant resistance, companies may eventually decide it’s too expensive and cumbersome to deal with so many “non-consenting interest owners.” At present, however, “the Colorado the Oil and Gas Conservation Act does not contain a minimum leased or participating acreage percentage requirement for a pooling order to be entered (thus, in theory, a 1% mineral owner could pool the other 99% owners),” Lepore wrote.

Mike Freeman, an attorney with Earthjustice, a non-profit environmental law organization, said that forced pooling laws were written long before “unconventional” gas plays allowed operators to access minerals from miles away. “The mechanism they’re using has really outlived its usefulness,” he said.

Law professor Kramer agrees that most legislation around the country has not been updated to consider new technologies and human settlement patterns. “Most pooling clauses contained in oil and gas leases were drafted with vertical well drilling in mind,” Kramer wrote. In a phone interview, Kramer said that some states have altered their laws to give more weight to the property rights of surface owners. Compulsory pooling laws are still prevalent around the country, he said, but are not inviolate. “If a legislature wants to redraw the balance given to people who don’t want to develop their rights,” Kramer said, “the legislature is free to do so.”

COGCC’s Lepore said that under current law, if the COGCC ascertains that the spacing is appropriate and the operator meets a couple stipulations, it normally grants such requests. Even homeowners who own their mineral rights have very few legal options to fight a company that wants to drill. “Essentially, an unleased mineral owner can object on grounds that the applicant failed to offer the mineral owner reasonable lease terms,” Lepore wrote, or if the lease didn’t allow homeowners to receive their fair share of the proceeds. In other words, simply not wanting it to happen in your backyard – even if you own the mineral rights – is not a valid legal reason to object.

“We didn’t even think it was possible to frack a neighborhood.”

Extraction spokesman Brian Cain recently sent a statement to the news media regarding his company’s Broomfield plans, stating that it chose locations “to be as far as possible from residential housing.” It promised to provide “professionally design [sic] landscaping, at each site before commencing activities to address visual impacts of these operations. The landscaping will involve rolling berms covered with natural grasses and trees inspired by Colorado’s flowing landscapes and vistas.” According to Cain’s statement, the company also planned “Best Management Practices and latest development technology” to “deliver the safest, cleanest, and best project to the community.” Cain did not respond to several emailed requests for further comment for this article, and his voice mailbox was full.

For many people living in residential enclaves like Wildgrass, applying the forced pooling provision in 2016 to a densely inhabited residential development where the vast majority of residents don’t want oil and gas drillers is unfathomable. “We didn’t even think it was possible to frack a neighborhood,” said Wildgrass resident Bernie McKibben, expressing a sentiment shared by a rapidly growing number of urban and suburban residents around the state.

The forced pooling news hit Wildgrass residents like a cannonball. “At first I really thought the High West letter was a joke,” said Stephen Uhlhorn, an engineer who bought a house in Wildgrass when he moved from Florida three years ago with his wife, a physician, and their two children. Like many of his neighbors, when Uhlhorn started looking into Extraction’s forced pooling plans, he went from disbelief to anger and defiance. “This is suburbia!” he said. “You don’t expect oil rigs in suburbia.”

Uhlhorn is bewildered by the state’s willingness to allow industrial facilities in neighborhoods where it would be tough to get approval to build a new Walmart. “What’s next?” he wondered. “Are they going to drill under the 16th Street Mall? Apparently, there’s nobody that’s going to stop them.”

As Coloradans continue to debate local control over oil and gas development, how far well pads should be set back from schools and water sources, and what limits, if any, should be placed on the fossil fuel extraction industry in residential neighborhoods, the Wildgrass case study stands as a sentinel and a warning: if state-sanctioned drilling can happen there, it can happen in any neighborhood in the state that sits atop viable quantities of hydrocarbons.

![Bernie and Linda McKibben, residents of Wildgrass. They are leading the anti-forced pooling efforts.]()

Bernie and Linda McKibben, residents of Wildgrass. They are leading the anti-forced pooling efforts.

Welcome to Broomfield: “A great place to live, work, and play!”

To understand Wildgrass residents’ concerns about turning their tranquil suburban community into an industrial zone, one only has to drive north along county roads on the east side of I-25 out of Denver. Interspersed among large, new housing developments built by the biggest developers in the country such as Lennar and KB Homes are clusters of mini-refineries barely hidden by hay-bale walls and camouflaged by tan barriers the thickness of corduroy. There, oil and gas companies have built multiple wellheads and dehydrators, separators, compressors, pipelines and storage tanks within a stone’s throw of suburban backyard barbeques, swing sets and elementary schools. All these industrial sites are vulnerable to leaks, spills and explosions, and emit an array of pollutants, including benzene, ethylene and methane.

State regulators have only the barest grasp of the kind and amount of emissions that escape these facilities. The COGCC does not regulate air emissions, and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Safety (CDPHE) only inpects well sites about once every five years. (SEE RELATED STORY: TEXAS TEA) Scientists have documented undetected leaks and inadequate methods of determining the scope of toxic releases. Researchers have documented multiple health impacts on people who live in close proximity to oil and gas operations around the country.

Nonetheless, Colorado state health officials still insist there is insufficient evidence to link exposures from neighborhood drilling to public health impacts in the state. Dr. Larry Wolk, the executive director and chief medical officer of the CDPHE (who is also a COGCC commissioner), recently told The Colorado Independent, “We don’t see anything to be concerned with at this point in time.”

Broomfield (population 65,065) is almost equidistant from where the Broncos play in Denver (15 miles) and the Colorado Buffaloes play in Boulder (10 miles). It has easy access to the Boulder-Denver turnpike, is about a 40-minute drive to DIA, and is home to consultants, professionals and business people who moved to this Front Range playground so they can ski on the weekends, send their kids to good schools and enjoy open spaces and views of the Continental Divide from their bedroom windows.

A Google-Earth-eye view of the Wildgrass development shows it as part of the swelling Denver metropolitan organism, with contiguous communities like Broomfield, Westminster, and Northglenn filling the remaining open spaces with tract homes and national chain strip malls. Broomfield itself has grown by almost 60 percent since the 2000 Census – three times the statewide average.

Entering Wildgrass a visitor drives past laser-carved sandstone that marks the neighborhood as distinct from the nearby laser-carved enclave, Silverleaf. Two-bedroom townhouses in the housing tract sell from the low $400s. Five-bedroom, 5,000-square-foot homes fetch $1 million. You pass the Holy Family High School, owned and operated by the Archdiocese of Denver (more on that later), which many Wildgrass children attend. On an early fall afternoon, Latino gardeners with leaf blowers patrol the yards, delivery vans unload new refrigerators and residents walk Labradors on leashes. It’s an unlikely spot for yet another new battlefront in the state’s fracking wars.

After Extraction’s sign-in-15-days-or-else letter circulated, a few upset residents wanted to know if they were alone in their outrage. They decided to take Wildgrass’s temperature, which is harder than you might think in a typical American exurban enclave, where people drive their Lexuses and Audis (and Priuses and Leafs) into garages adjacent to their homes, and rarely socialize as a community.

One resident, Bill Young, is an IT consultant who created an informational website about the drilling proposal, then conducted an online poll. About 300 of the 510 homeowners responded, he said, with 75 percent opposed to any oil and gas development and ready to fight. Among the remaining 25 percent, most said they felt like the deck was so stacked against them that resistance would be futile – and expensive.

A handful of residents happily signed on to Extraction’s plans.

Ryan Nygard, who moved here from Canada two years ago and who’s been working in the oil and gas industry for 12 years, said that many of his neighbors’ concerns about health and safety are overblown. “I have no problem with it,” he said, adding that he doesn’t dispute that a majority of his neighbors oppose Extraction’s plans. Nygard said that there’s a bit of a hypocrisy factor at play here as well, since most Wildgrass residents take hot showers and heat their homes using natural gas and drive their cars to the mountains to ski. Nygard also believes that there is more support for his position than has been expressed publicly – what he called the “Trump factor.” Nygard said he signed the proffered lease with Extraction – after he made sure it wasn’t a hoax.

A few Wildgrass residents hoped they’d receive six-figure annual payouts for agreeing to let their land be drilled. Yet those expectations are far out of line with Young’s estimates, based on information provided by Extraction, which put royalties for an average Wildgrass homeowner with a quarter-acre lot at about $3,000 over the first four years and maybe $100 a year after that. That’s hardly Beverly Hillbillies money.

Among those who became part of the de facto organizing committee against Extraction’s proposed development are Linda and Bernie McKibben. The couple moved to Wildgrass from Phoenix about 10 years ago with their two children. Bernie is an electrical engineer who’s worked in the mobile phone sector, and Linda is a 30-year veteran nurse who’s worked in many different healthcare settings, from cardiac care to home health. Neither self-identifies as environmental activists, and they are dumbfounded by the energy industry’s television ads that paint outraged suburbanites as “fracktivists.”

Linda notes that Wildgrass’s own covenants, codes and restrictions include a host of limitations of what residents can do with their property, from where they can park to what color they can paint their mailboxes. “There are all kinds of restrictions on what you can do here,” she said, “apparently unless oil and gas companies want to do it.”

The community sought legal advice. They couldn’t find a lawyer to take the case at first, either because the lawyers they consulted worked with oil and gas companies, or because even sympathetic lawyers said the law allowed forced pooling of non-consenting mineral owners, no matter how crazy it sounded to some Wildgrass residents.

They hired attorney Matthew Sura to give them a Forced Pooling 101 tutorial. He wasn’t optimistic, either. According to the documents Extraction had filed, the company wanted to drill up to 42 wells on the Lowell Pad that was north of Wildgrass but not technically on neighborhood property. The area to be horizontally drilled will also head towards the Anthem development to the north (where homebuyer James Sines had declined to buy), as well as land owned by the City of Broomfield and the Archdiocese of Denver to the south.

Extraction had gained the surface rights to drill from four spots along the Northwest Parkway corridor; the closest is a half a mile from Wildgrass but other locations will be less than 600 feet from the nearest Anthem house, across the highway. In its application to the COGCC for the Wildgrass development, Extraction listed ten pages of “unleased mineral owners.” Extraction had already received provisional support from elected officials in Broomfield, which is both a city and a county, even though its citizens had narrowly voted to institute a five-year fracking ban in 2014 that was annulled by the state Supreme Court in May.

The upshot, attorney Sura told Wildgrass residents, was that “there was no statutory way to fight this,” and suggested using lease negotiations to limit the impacts on the community.

Wildgrass residents said they needed some time to digest all of this and organize. They successfully lobbied the Broomfield City Council to support their request to postpone a “spacing hearing,” a process that helps determine how many wells can be drilled in a specific parcel of land, which was originally scheduled for Aug. 29. The COGCC agreed, and the hearing was rescheduled for Dec. 12. On Monday Nov. 28, the hearing was rescheduled again, for Jan. 30, 2017.

If the spacing is approved, as expected, a forced pooling application will likely follow.

In a phone interview, Broomfield Mayor Randy Ahrens, who describes himself as “an oil and gas guy” from his years as an engineer in the industry, said he is “appalled” by Extraction’s plans on several counts. First, Broomfield purchased the mineral rights near its reservoir from Noble Energy years ago because “we didn’t want to worry about oil wells” close to a water source. “We didn’t buy them so somebody else could force pool them,” Ahrens said. Second, in Extraction’s initial negotiations with the city, the company offered to consolidate several dozen well pads down to four, with a total of 40-50 wells. Now it appears that Extraction is planning up to 140 wells. “I’m appalled at the size of the operation,” said Ahrens, which would create a “major industrial site” that doesn’t fit with the nearby residential neighborhoods, including Wildgrass and Anthem. Ahrens said he doesn’t hold out hope that the COGCC will intervene, since “they’re going to rubber stamp anything.” Broomfield is exploring its options, Ahrens said.

![Current Extraction Oil well in the open space west of Wildgrass. Extraction says they will close this well.]()

Current Extraction Oil well in the open space west of Wildgrass. Extraction says they will close this well.

Making a PowerPoint

When Extraction executives heard that Wildgrass residents were going to speak with attorney Sura in July, they tried to invite themselves to the meeting. Instead, residents agreed to arrange a separate meeting with Extraction representatives.

By the time Extraction presented to the Wildgrass residents at the Broomfield Rec Center on July 25, many residents were still seething over the strong-arm tactics of the initial High West letter. Others were frustrated that they had to deal with this at all and wished Extraction would just go away.

About 80 residents milled about before the meeting, sampling pastries and coffee provided by Extraction. Casually dressed (pressed khakis and white shirts, no ties) men from Extraction stood around posters with maps of Wildgrass and the proposed drilling sites, answering questions.

The 7 p.m. start time came and went, and the crowd grew restless as the main presenter, Boyd McMaster, fiddled with a recalcitrant PowerPoint presentation. About 45 minutes into the scheduled two-hour presentation, the presentation sprung to the screen. This was not a good sign to many of the attendees, who texted incredulous remarks to each other. “This is the company we’re supposed to trust with drilling under our bedrooms?” wondered IT consultant Young.

McMaster affably laid out Extraction’s plans to the skeptical audience, promising a question-and-answer session at the end. He said that many of Extraction’s employees lived in the area, and he understood there were concerns. “We’re not in the middle of the prairie here,” he said. “We’re in the middle of your community.” McMaster said that he and his team would always be available to answer questions, and shared contact information with the crowd.

He described how they would use horizontal drilling methods to minimize the number of well pads. They would cap several older wells scattered around the county. They would build tall sound walls during construction and would follow the letter of the law. “Colorado has the strictest regulations of this industry than any place in the world,” he said, parroting the industry’s stay-on-message message.

If the industry has been fracking this way for 60 years, then the Dodgers are still playing in Brooklyn.

Then he took on the “F-word,” fracking, by calling it “hydraulic stimulation,” and said that the industry has being doing it for 60 years. This implies that nothing is different between the way companies drilled when Dwight D. Eisenhower was president and the recent technology revolution that allows companies to unlock mile-deep “tight-sands” reservoirs of hydrocarbons using millions of gallons of water mixed with chemicals and biocides. If the industry has been fracking this way for 60 years, then the Dodgers are still playing in Brooklyn.

New technology has driven an unprecedented oil and gas boom (and bust) over the past decade – in Colorado and around the world. The boom slowed after a precipitous drop in oil prices (oil plummeted from more than $100 a barrel in April 2015 to less than $30 a barrel early this year before rebounding to around $50 recently), but has not halted companies like Extraction from preparing for a further price rebound. On Tuesday, Oct. 11, Extraction Oil & Gas held an initial public offering of 33.3 million shares of its stock on Wall Street. The estimated value of the company exceeded $3 billion.

In the taxonomy of oil and gas companies, mid-sized operators like Extraction fill a niche that investors might characterize as bold, but others call inherently antagonistic. “They take toxic assets that other people have walked away from and develop them,” said an independent operator who says Extraction is being overly aggressive in residential communities. The operator declined to be named because he works with one of Extraction’s shareholders.

When it became clear that Extraction’s presentation was going to continue until the attendees’ babysitters would expect to be relieved, one resident asked about the promised question-and-answer portion of the show. McMaster started riffing through FAQ questions he had written down before the meeting. When a resident insisted that Extraction take questions from the live audience, McMaster did.

One resident wondered where Extraction would get the water to do the fracking and where the produced water would go, referring to the byproduct of fracking that includes millions of gallons of hydrocarbon- and chemical-laced water that needs disposal. Would Extraction pipe it or truck it to injection wells? Where were those? Weren’t injection wells the cause of earthquakes, like what was happening in Oklahoma?

The vague answers McMasters gave were disconcerting. The produced water, he said, would be taken to an injection well in Weld County, at least 12 miles away. That didn’t help much, said Sally Kaplan, a Wildgrass owner who attended the meeting. “They didn’t tell us where they were going to get the water from, or where the wastewater was going to be stored.” Just because it wasn’t going to be dumped in their backyard, Kaplan said, “doesn’t mean we don’t care about it.”

Others wanted to know about the project’s timing. Although it only takes a few weeks to drill each well, McMaster told them, there would be quite a number of wells drilled from the pads, and construction would probably take about two years.

That only made some residents even more nervous about their home prices and peace of mind. On a table along with Extraction’s brochures was a letter addressed to the Broomfield City Council and signed by six “concerned realtors.” The letter stated that the proposed oil and gas operations “will have a profound impact on the surrounding property values and the quality of life for Broomfield residents.”

The Extraction meeting didn’t allay many Wildgrass residents’ concerns about safety, nuisance, stress, health complaints, air quality issues, impacts to water quality and availability and effects on their children and property values. “We were supposed to say, ‘We’re the one percent, we love hydraulic stimulation and we love America,’” said one homeowner, who declined to be named because of the sensitive nature of their job. “That’s not gonna happen.”

It didn’t take long after the July meeting for residents to take McMaster up on his offer to answer their questions. At least five residents said they never received replies.

“Nothing but radio silence,” Uhlhorn said.

![View from the Lowell Pad, looking NE across Anthem, where Extraction Oil & Gas plans a 42-well site, between Wildgrass and Anthem developments. The drill pad would reach under Anthem and it's open space.]()

View from the Lowell Pad, looking NE across Anthem, where Extraction Oil & Gas plans a 42-well site, between Wildgrass and Anthem developments. The drill pad would reach under Anthem and it’s open space.

Moving to “Doomfield”

At Wildgrass, resistance to forced pooling doesn’t seem to follow partisan lines. Unlike Boulder County, the enduringly liberal Democratic enclave to the west, Broomfield has more unaffiliated voters (16,250) than registered Democrats (13,020) or Republicans (12,550). Issues like local control, property rights and government bullying resonate pretty strongly among Republicans, and issues like environmental protection and climate change are trademark Democratic issues.

Wildgrass residents fanned out to gather information, employing an array of tripartisan expertise from lawyers, accountants, financial analysts, healthcare professionals, engineers and others among them. Many are reluctant conscripts, like IT security consultant Young, who has lived in Wildgrass since 2010. “It took it landing in my backyard for me to get involved,” he said.

However grudgingly, Young joined the fray and started researching. He noted that in the Extraction presentation, “there was not a single slide about surface spills.” So he conducted his own search and discovered seven reported surface leaks in Broomfield in the past five years from other operators. Perhaps even more disturbing for Young, the city of Broomfield’s Public Health and Environment Division had documented that last year, 22 out of the 38 active oil and gas sites in Broomfield had leaked. Neither the COGCC nor the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment had detected the leaks.

Extraction, Young discovered from COGCC documents, had 17 documented spills and releases around the state (this did not include two recent spills in November), several of them due to “human error.” He also learned from the COGCC website that there had been 66 complaints filed against Extraction for everything from noise and odor to increased traffic from trucks carrying equipment to and from drill sites.

Other residents started digging into water issues. Hydraulic fracturing requires large amounts of water, and also “produces” water that comes up co-mingled with the mile-deep oil and gas. One new well pad would be located between an existing reservoir and a planned reservoir, meant for recreation as well as for city drinking water storage.

Wildgrass residents reached out to the Archdiocese of Denver, which owns land and mineral rights adjacent to Wildgrass under Holy Family High School. Since Pope Francis expressed concern about climate change and environmental stewardship in his Encyclical in May 2015, Wildgrass residents thought there might be some opening to find an ally in the Church.

Initial outreach to the Archdiocese was met with a cool response, so Wildgrass residents printed up a flier with the headline in red, bold caps: FRACKING UNDER HOLY FAMILY SCHOOL and distributed it to parents.

Wildgrass resident Jean Lim, a professor at the Jesuit-run Regis University, says that the impacts on her family worry her, but that there are also larger issues to consider. “The Pope’s Encyclical was a strong statement of environmental concerns on a global scale,” Lim said. “It should have the serious attention of all Catholics.” Lim said she has contacted the Archdiocese, and expressed an interest in arranging a meeting to discuss ways to work together to “secure health and safety protections for its high school students and the Catholic residents of Wildgrass.” Lim has not received a reply.

A Denver Archdiocese spokeswoman, Karna Swanson, declined to comment on how or whether the Holy Father’s Laudato Si’ would be taken into consideration as part of the Archdiocese’s decision about whether to accept or oppose Extraction’s leasing offer. “We were approached by Extraction Oil & Gas to lease our mineral rights,” Swanson confirmed. “We at this point are not doing anything. We haven’t responded.”

If our country’s energy independence and state economy relies on drilling in neighborhoods like Wildgrass, “We are way on the wrong track.”

Linda McKibben, a registered nurse, started investigating health impacts and found an alphabet soup of federal and state agencies and universities that have published data about the negative health impacts of oil and gas development, including NIH, CDC, EPA, OSHA, NIOSH, CDPHE, CU, CSU, Cornell, Duke and many others. “There is a lot of literature suggesting there are legitimate health concerns for workers and communities near these developments,” she concluded. “It defies understanding,” she said, how state regulators could agree to let residents act as guinea pigs while epidemiological evidence accumulates around the country.

Bernie McKibben started looking further into the COGCC’s role in overseeing oil and gas operations in the state. At first, he had believed Gov. John Hickenlooper’s assurances about the state’s ever-tightening regulations and inspections. He had taken heart from the COGCC’s legal mandate to, “foster the responsible, balanced development, production, and utilization of the natural resources of oil and gas in the State of Colorado in a manner consistent with protection of public health, safety, and welfare, including protection of the environment and wildlife resources.”

But then Bernie started understanding just how little the industry was regulated, how rarely inspectors made visits, and how haphazardly companies monitored their own sites. He got a hold of the “Field Inspection Unit Well Inspection Prioritization” document from the COGCC, which he said floored him on multiple fronts. The document prioritizes a “risk-based strategy for inspecting oil and gas locations,” categorizing operations by risk factor and giving each a rating according to its level of importance. He discovered that “Population Density & Urbanization” only accounted for 10 percent of the weighted assessment. He found the fine print was even more appalling: The highest density the COGCC considered was in places where there were 25 people per square mile or more. This means that a semi-rural area like Clear Creek County is treated the same as Broomfield County, the second-most densely populated county in the state, with more than 1,700 people per square mile.

“Looks to me like people in subdivisions like Wildgrass aren’t very high on their priority list,” he said.

Another front on the Wildgrass fracking wars opened up with lawyers who lived in the neighborhood and who started scrutinizing the fine print regarding liability. They found that residents who signed the leases could be held responsible for Extraction’s legal costs and other financial consequences if there was an accident. “We would be accountable for their errors?” asked Bernie, incredulously.

Residents sought allies in the other Broomfield neighborhoods. The nearby Anthem subdivision had generated its share of concerned citizens, since Extraction was heading their way as well. Some Anthem residents owned their minerals, but many did not.

At a Broomfield City Council meeting on Nov. 15, about 40 Anthem residents showed up to urge the mayor and council to protect them. The scale of Extraction’s plans, which had ballooned to 140 wells, was unprecedented, former oil and gas worker Lara Hill-Pavlik told the commissioners. “I am unaware of a single project of this magnitude which has been implemented in such close proximity to schools and residents,” she said. “And I lived in Houston.”

“I told my husband, ‘We’ve moved to Doomfield.’”

After the meeting, Anthem resident Michael Kohut said, “We’d like to set a different precedent: saying no to drilling in residential neighborhoods.”

Patricia Romero-Trustle, who told council members that she recently moved from Los Angeles for a better quality of life, stood in the municipal building lobby after the meeting completely disillusioned. “I told my husband, ‘We’ve moved to Doomfield,’” she said.

Broomfield City Councilman Kevin Kreeger heard the Anthem residents’ presentation, and is outraged at the whole concept of forced pooling – as well as the way Extraction has played its pooling card. “Forced pooling is big government and big business at their absolute worst,” Kreeger said, since it grants the state government the right to take one person’s property and give it to a company, even when “there is no social benefit of any kind.” He said that “Extraction has not operated with integrity or respect for our community,” and is disturbed that the company keeps increasing the number of wells it intends to drill. Originally, the plan was to drill 24 new wells after plugging and abandoning 26 old ones, Kreeger said. Now, Extraction has applied to drill almost six times that many, all of them near homes and schools. “That many wells means 24-hour drilling for years,” he said.

![Wildgrass residents gathered in one of their community playgrounds to show their resistance to the planned forced pooling action by Extraction Oil & Gas.]()

Wildgrass residents gathered in one of their community playgrounds to show their resistance to the planned forced pooling action by Extraction Oil & Gas.

NIMBY and beyond

Wildgrass organizers heard a long list of reasons why residents and neighbors opposed Extraction’s plans. They ranged from NIMBYism to health impacts to an awakening that there’s a much bigger issue at play here, including the climate impacts of continuing to go full-speed ahead with fossil fuel development — even when there’s a gas glut and overwhelming evidence that human-caused climate change is already affecting Colorado in multiple ways. If our country’s energy independence and state economy rely on drilling in neighborhoods like Wildgrass, the engineer Uhlhorn said, “We are way on the wrong track.”

Not all Wildgrass residents are convinced they can beat Extraction or want to fight the COGCC. Even those who do not support Extraction’s efforts worry that community members are spending time and treasure on a losing battle. Peter Pacek, a healthcare executive and nine-year resident of Wildgrass, said he’s concerned that there is “very little that an average citizen can do to hold them back because of the way the laws are written.” Still, Pacek said, he didn’t sign a lease, either.

Residents will soon hear what the COGCC has to say about the next step, when the Extraction faces a usually pro forma “spacing hearing” now scheduled for Jan. 30, 2017. For the time being, the discerning homebuyer James Sines said this week, he’s pulled his house from the market, waiting for the next shoe to drop.

Despite the COGCC’s long record of accommodating the industry, Wildgrass residents now know they are not alone: Their Anthem neighbors, as well as people in Greeley, Boulder, Ft. Collins, El Paso County, Battlement Mesa, Pueblo, Thornton, Longmont, Lafayette, Westminster and dozens of other communities around the state are all struggling to keep this rising residential hydrocarbon tide from swamping their neighborhoods. “We know that if we’re going to have any hope, we have to act as a group,” said Bernie McKibben.

The group is likely to grow. When several Wildgrass residents met with COGCC Director Lepore recently, they asked him where they could move in Colorado to avoid having to fight oil and gas development.

His reply: “Summit County” — a place so mountainous, it would be nearly impossible to drill.

Cover image: Homes in Wildgrass as seen from open space to the west.

All photos by Ted Wood/The Story Group

That midday October exchange in the back of the Alpine Rose Cafe encompasses much more about what’s at stake in the year’s legislative races across Colorado than the two men might realize.

That midday October exchange in the back of the Alpine Rose Cafe encompasses much more about what’s at stake in the year’s legislative races across Colorado than the two men might realize. Out on the campaign trail— as much as there is one across this vast landscape— Crowder doesn’t get into the larger picture with voters about what’s at stake at the Capitol in his race.

Out on the campaign trail— as much as there is one across this vast landscape— Crowder doesn’t get into the larger picture with voters about what’s at stake at the Capitol in his race.  If Casias wins, “It’ll mean a lot for the Democratic Party,” he acknowledges. “However, though, parties don’t elect me, people elect me.”

If Casias wins, “It’ll mean a lot for the Democratic Party,” he acknowledges. “However, though, parties don’t elect me, people elect me.”